Why Steve Jobs didn't need a script

Lessons from the creator of the iPod, iPhone, Nest

Most nonfiction books cover one solid idea stretched over 300+ pages. But then there are rare gems like Build that cover dozens of big ideas. In fact, Tony Fadell — the man behind the iPod, iPhone and Nest — has so much juicy content I only wish he could’ve dived deeper in places.

So I’m covering four passages from the book that deserve more attention:

The problem with career advice

The little screwdriver that helped Nest go viral

Why Steve Jobs didn’t need a script

What really went down when Google bought Nest for $3.2B

But first, a word from our partner:

Create once, publish everywhere. This is the holy grail of making anything these days. Turns out there is a neat solution — it’s headless content management.

If you’re curious about the hype around headless like I am, Storyblok has a new report that gives you the cheatsheet on this rising trend:

The problem with career advice

Every piece of advice should come with a disclaimer: this worked for me, but it may not work for you. Not only is advice derived from personal experiences, they are disproportionately shaped by extreme anecdotes. Something is worth sharing because it turned out extremely good or bad. Ironically, these are the hardest to apply because… they’re not that common.

It’s better to take note of patterns and connect your own dots. So here are some patterns to consider:

Try to get into a small company. The sweet spot is a business of 30–100 people building something worth building, with a few rock stars you can learn from. You could go to Google, Apple, Facebook, but it’ll be hard to maneuver yourself to work closely with the rock stars.

Talent density is probably the best reason to leave a cushy job for the chaos of a small startup. Contrary to what companies will tell you, the truth behind growth is that they’ll eventually bring on people who are just ok. It’s impossible, even unnecessary, to fill every seat with rock stars when the business is roaring.

The smaller the team, the more you get to see the full operation. Instead of being responsible for a few pixels, you’re responsible for a good part of the business. You get to take more projects from start to finish in a shorter span of time. While it’s hard to predict which startup will mint you a fortune, high talent density will at least guarantee that you’ll get useful learnings and make valuable connections.

People often ask: is now the right time? Well, there are wonderful gems in awful economies and awful duds in wonderful economies. The problem with the latter is that it’s harder to separate duds from gems because everyone’s getting funded.

The itch to time the market is understandable if you’re planning to cash out fast. But when it comes to equity that takes many years to become liquid, short-term timing is less relevant. So the million-dollar-question isn’t: is now the right time? But rather: is this the right startup?

How Nest went viral

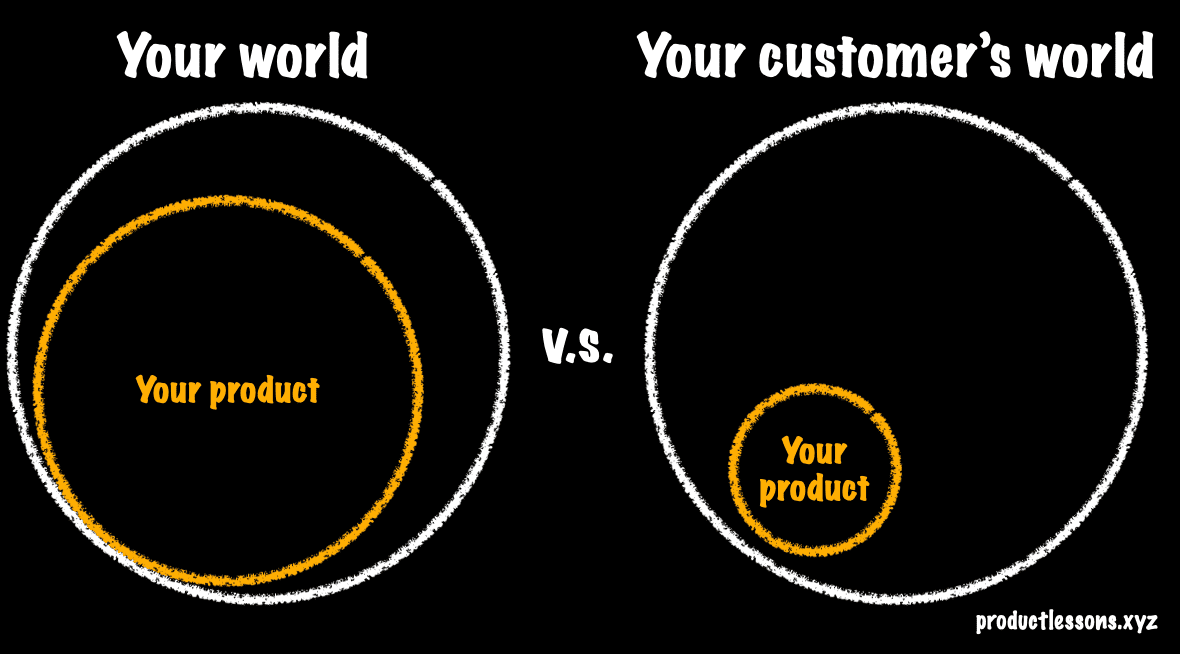

When you’re heads down building, your product is your world. It’s the most special thing to exist. But customers have no clue, nor do they care:

Customers need reasons to pay attention at every step. This is how Nest stumbled on a detail that paid off big-time.

While testing V1 of their thermostat, they realized that installation was unpredictably painful because people first needed to find a screwdriver in the house. Instead of putting the burden on customers, Nest included a screwdriver in every box. But they took it one step further:

We included four heads — more than anyone needed to install the thermostat — so that people could use it for practically anything. So that Nest stayed in their brains as long as the screwdriver stayed in their drawer. Longer.

The best marketing doesn’t feel like marketing at all. They’re not splashy ads. They’re not forced endorsements. They’re unexpected moments of delight that get people sharing. What I find impressive is that Nest turned a frustrating step into a special moment, reminding us that it’s always possible to write a great last chapter.

Why Steve Jobs didn’t need a script

Whenever we’re blown away by the quality of someone’s work, it’s usually because we’re seeing the final polished version, not all the clumsy drafts that came before:

Steve had been telling a version of that same story every single day for months and months during development — to us, to his friends, his family… Every time he’d get a puzzled look or a request for clarification from his unwitting early audience, he’d sand it down, until it was perfectly polished.

Why does this thing need to exist? Why does it matter? Why will people need it? Why will they love it?

Genius is right there on display for everyone to admire. Toil is hidden behind closed doors. I’ve learned a productive way to appreciate genius is to recognize that the grind comes before the gold. Jobs was an exceptional showman, but he also worked at it obsessively.

The $3.2B marriage

Acquisitions are basically expensive marriages, which makes founder departures a fascinating study of divorce. Tony famously left Google only 2 years after they bought Nest for $3.2B:

When Larry told me during acquisition that Google would marshal the team and align their priorities with ours, he was 100% telling the truth.

But what that looked like at Google was giving the team the skeleton of a plan and letting them fill in the rest as they went. But I had interpreted his words through an Apple lens. If Steve Jobs said he was going to marshal the team, that meant he was going to be there every step of the way — weekly, sometimes daily.

When a promise is broken, the default interpretation is that the person lied. The more charitable interpretation is that they had a different understanding of the promise.

This sounds like BS, yet time and again I’ve seen people say the same words but mean different things. One of the culprits is corporate speak. Corporate speak can be so vague and sweeping that everyone hears what they want to hear. Marshal the team, align priorities, do what’s right by customers. Who can argue against these? Nobody — they’re platitudes.

The burden is on us to clarify, and drive towards specifics. What does marshaling the team look like? Who’s involved? Who decides? What happens when people disagree on priorities? How was it resolved the last time it happened?

Sometimes there are irreconcilable differences: Tony’s view of how teams work was heavily inspired by Apple under Steve Jobs — a tops-down autocracy. Google, meanwhile, is known for their bottoms-up democracy. It’s like mixing oil and water.

Most people and companies need a near-death experience before they can really change.

Apple nearly died multiple times. Google’s been riding the advertising gravy train for decades, so there’s been little need to question the Google-y way. Are they successful because of their culture or despite their culture? Nobody can know for sure.

What is for sure: to make informed decisions, dig beneath the veneer of corporate speak; figure out what struggles shaped the beliefs of people and companies you’re looking to join.

Recap

Don’t index too heavily on advice formed by extreme events; instead, learn from many examples, and connect your own dots

The best marketing comes from unexpected moments of delight that people can’t help but share

Genius is intimidating, until you realize they toiled over clumsy drafts to get to the final version you’re admiring

People can say the same words but mean different things; ask for specifics and figure out what struggles shaped their beliefs

For more stories, try Tony Fadell's book — worth the read!

This newsletter grows because of you! 🤗 Share with a friend, or if you’re new, subscribe below:

One last thing: here’s my toolkit to grow your product career. Get the shortcuts that took me years of work to figure out.

As always, thank you for reading!